U.S. Comic Books and the Police-Imaginary Complex

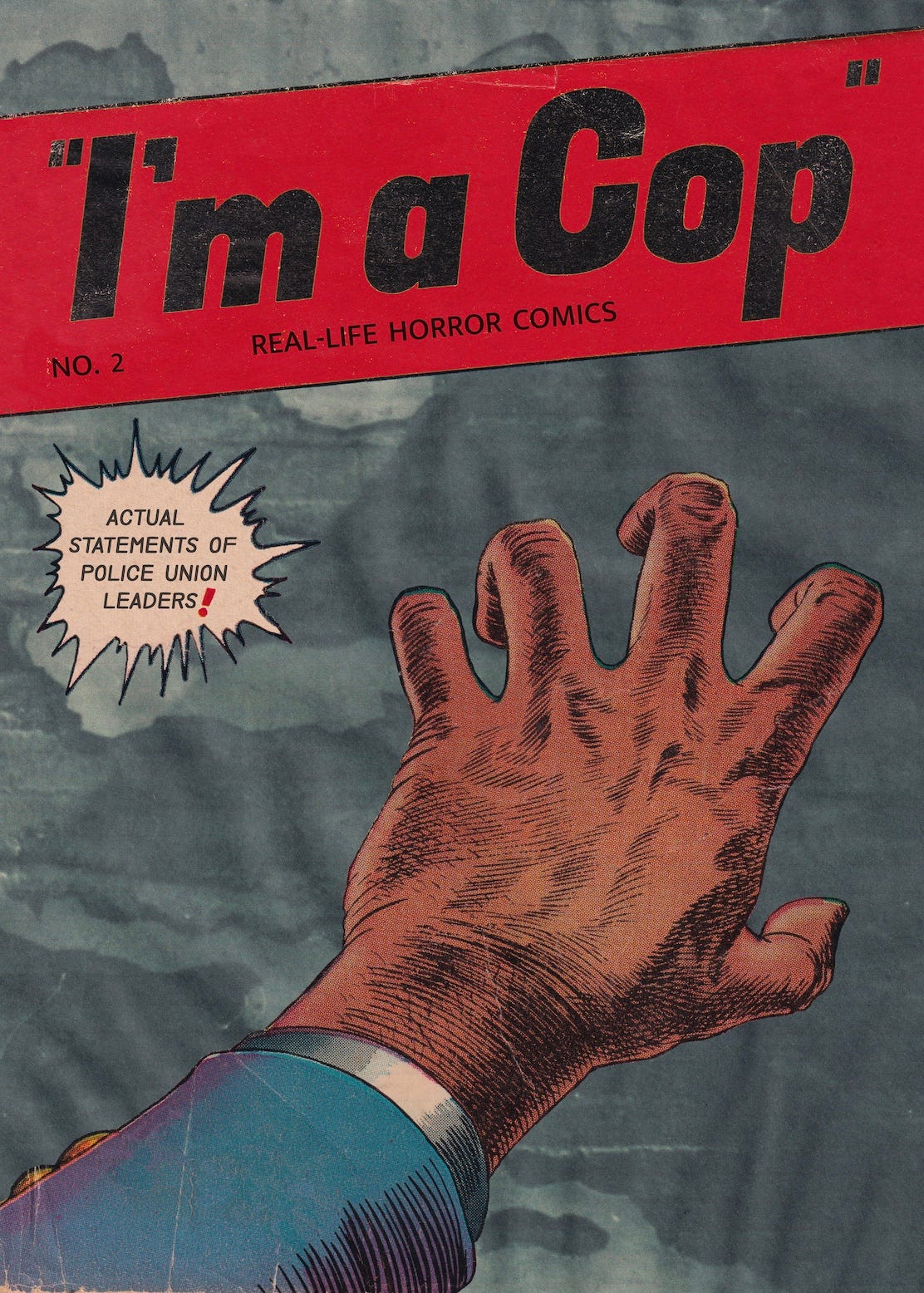

This essay originally appeared as the Afterword of “I’m a Cop”: Real-Life Horror Comics Vol. 2.

Let’s make one thing clear: the police seek to control our imaginations, and comic books have historically aided them in this goal.

The vast majority of U.S. residents encounter fictional depictions of the police more than they encounter them in their daily lives. While there are huge disparities in policing dictated by race, socio-economic standing, the neighborhood in which you live, and other factors, the sheer amount of images of policing that exist in U.S. popular culture suggest that the POLICE-IMAGINARY is at least as powerful a force in the public perception of the police as the police are themselves.

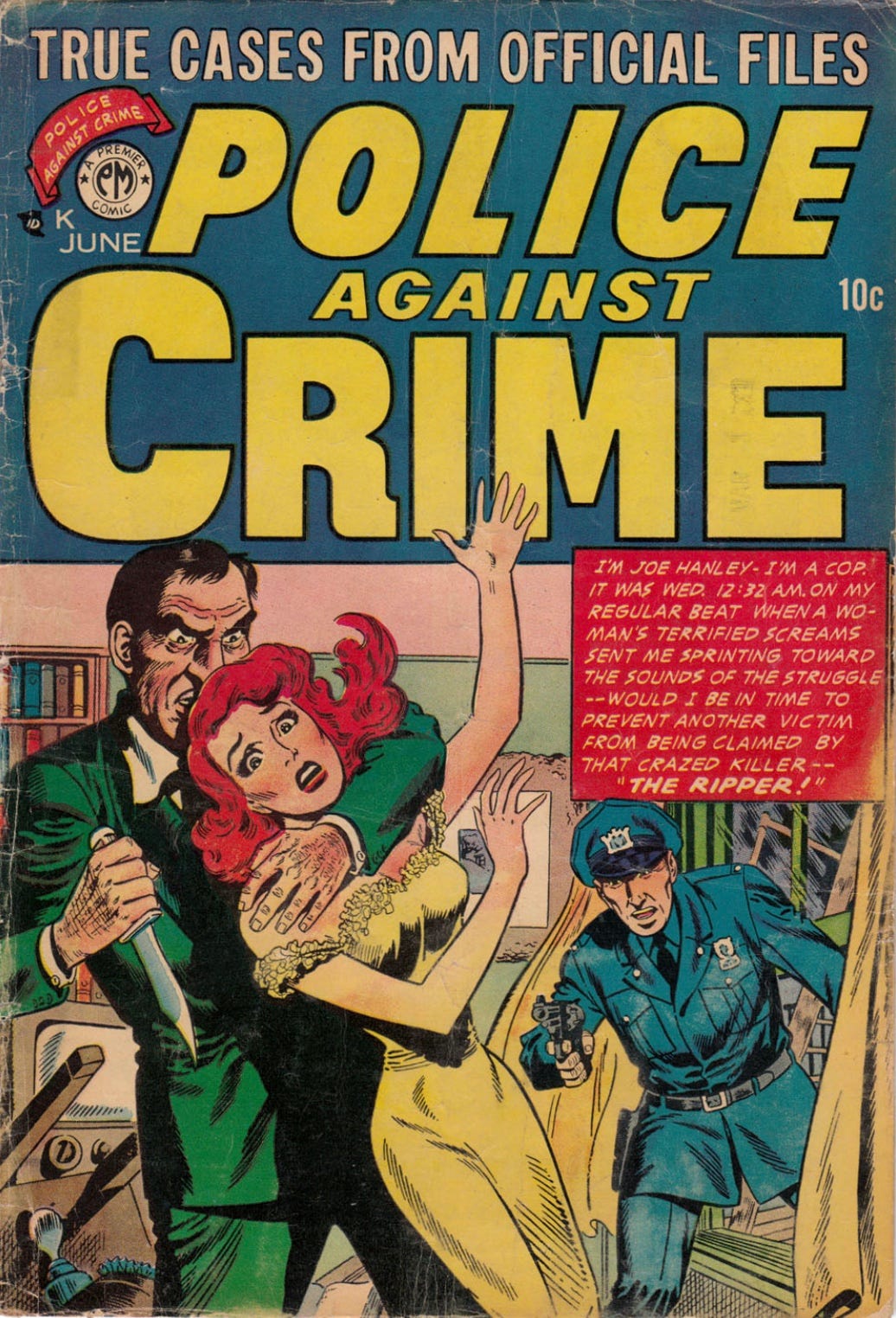

And this is where comic books come in. In the wake of World War II, when superhero comic books fell out of fashion, crime comics were one of the genres that most successfully took their place. Dozens of titles such as Crime Does Not Pay, Crime Must Pay the Penalty, and Police Against Crime sold tens of millions of copies each month. Looking at these comic books now, we see that they share almost identical themes with the public statements of today’s U.S. police unions: they depict crime as an out-of-control viral threat, they preach fear as the only sensible response to modern life, and in the words of union president Ed Mullins, they argue that cops are “all that stands between GOOD and EVIL.”

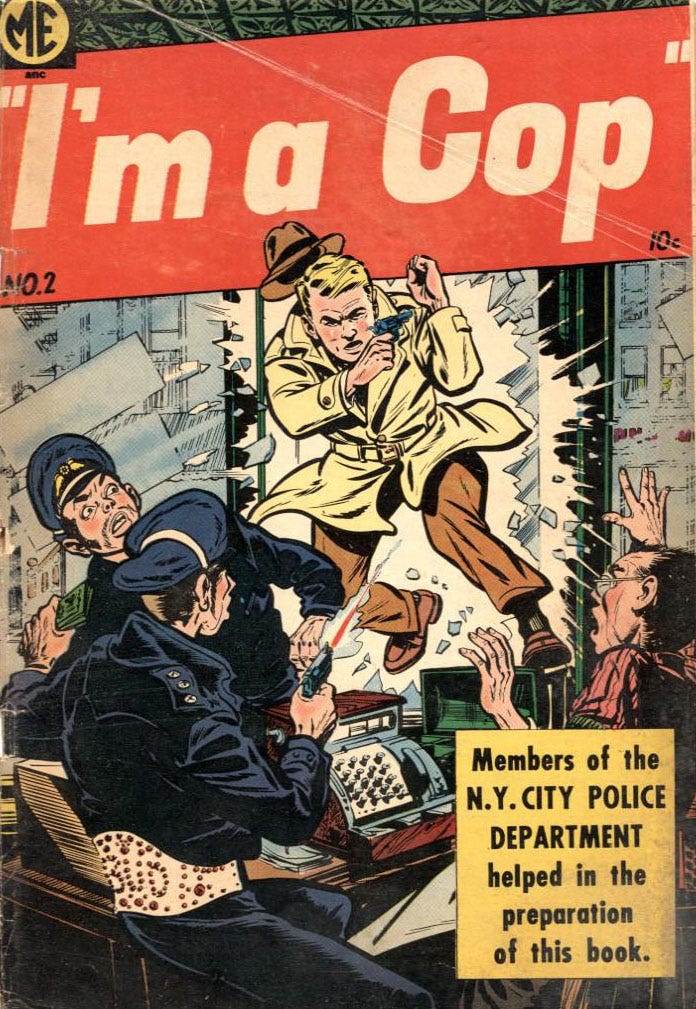

Comic books are, of course, only small component of the vast copaganda machine which dominates U.S. culture—also including mainstream news outlets reporting on “crime” and the cop television shows that remain the most popular genre in the history of their medium. This is quite literally by design. Since the days of Dragnet, police departments have employed PR divisions who work directly with television and film productions, as well as with comic book publishers. The title of the comic book you are reading, “I’m a Cop”, was taken from a 1954 crime comic which boasted on every cover, “Members of the N.Y. CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT helped in the preparation of this book.”

Direct connections between comics publishers and U.S. policing have been maintained ever since, as seen in the example of Spider-Man. In the 1970s, the Nixon administration enlisted Stan Lee to create a storyline in The Amazing Spider-Man which helped launch the disastrous “war on drugs,” and in the 1990s, the Clinton administration gave out anti-drug Spider-Man comics in schools. In a 2018 Spider-Man video game, the superhero worked directly with (and for) the NYPD, with players being required to repair dozens of NYPD surveillance towers in order to beat the game.

Spider-Man isn’t alone in his promotion of U.S. policing. A startling number of comic book superheroes work or have worked as cops—Green Lantern, The Flash, Hawkman and Hawkgirl, Nightwing, Batgirl, the Question, etc.—and superheroes as a whole represent a fantasy of vigilante super-policing. Why else would so many cops and police departments have adopted the logo of the ultra-violent character The Punisher—his signature skull combined with the “thin blue line” flag—as their own?

While current superhero and other mainstream U.S. comic books are often less blatant in their copaganda than in the past, we can’t ignore that copaganda, with its promotion of the fear of others and the necessity of state violence, remains a central pillar of the industry. The messaging of U.S. police unions and U.S. comic books appear synonymous. They seek to define our fears for us. They name our monsters, and crucially, they insist that these monsters are not the police themselves.

It isn’t a coincidence that you so often hear police refer to themselves as the “thin blue line” or the “line between good and evil.” The POLICE-IMAGINARY is dependent on clear binaries that separate “us” (most often coded as white) from those we should be afraid of (most often coded as black and brown). And to be clear, I’m positive that Ed Mullins of the New York Sergeants Benevolent Association, Joanne Segovia of the San Jose Police Officers’ Association, and Patrick Rose of the Boston Police Patrolmen’s Association would never imagine themselves as standing on the other side of that line, on the side of “criminals.” They might have been stealing from their union, smuggling fentanyl, and raping children, but they would never see themselves as the “evil” they’ve spent their careers warning us against.

Which suggests that this “line” is bullshit—a purposely destructive fiction. The POLICE-IMAGINARY exists to prevent community building and to promote the belief that the only untouchable governmental funding is for cops and the military.

So, again, let’s be clear. Comic books have played a central role in the creation of the POLICE-IMAGINARY, and for this reason, comic books have an obligation to help drive the POLICE-IMAGINARY out of our heads.